In spite of claims by Donald Trump that he won the 2024 election with an unprecedented and powerful mandate, the November contest came incredibly close to yet another misfire election where a candidate wins the Electoral College vote, but loses the national popular vote. Had less than 1 percent of voters in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan changed their vote to Kamala Harris, she would have won 270-268.

Despite Joe Biden earning 7 million more votes than Trump in 2020, a change of 20,000 votes in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Arizona would have resulted in an Electoral College tie–which Trump likely would have won in a contingent election. The resulting post-election campaign witnessed Trump pressuring state legislatures to choose their own electors, an “alternate elector” scheme, and Trump’s lobbying of Mike Pence to reject electoral votes. We find these shenanigans have left lingering effects upon many voters and have sewed additional distrust in the Electoral College process.

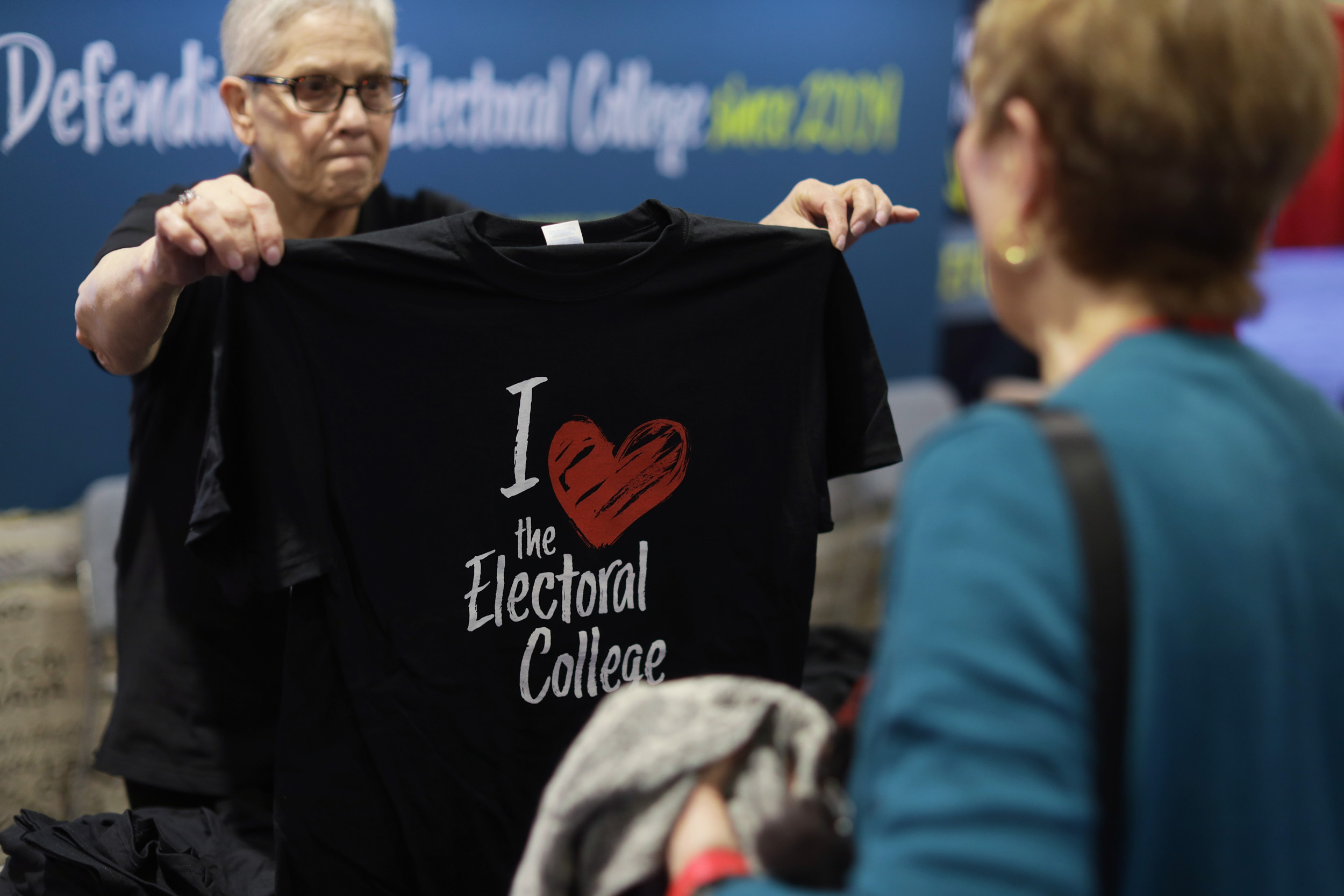

Alex Wong/Getty Images

The Electoral College is a frequent target of criticism—with more attempts to amend or abolish it than any other feature in the Constitution. Few polls ask citizens their thoughts about the Electoral College beyond one’s preference for a popular vote instead of the current process. Our poll of Ohio voters suggests there is likely much more concern among large majorities of citizens about potential hijinks than is often thought.

We find a majority of respondents (54 percent) would prefer a national popular vote over the Electoral College. Just about a third (35 percent) prefer the current Electoral College system. This is consistent with national findings from the fall where 58 percent favored a national popular vote and 39 percent favored the Electoral College. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we see a major partisan difference with 81 percent of Democrats preferring a national popular vote with just 34 percent of Republicans preferring so.

Misfire elections where a candidate wins the Electoral College vote but loses the popular vote have occurred in more than 10 percent of all presidential elections including Donald Trump’s victory in 2016 and George W. Bush‘s victory in 2000.

Our respondents were concerned with the possibility of misfire elections by a 2-1 margin (62 percent to 33 percent). Had Harris squeaked out victories in the three states we mentioned above, we imagine the desire to move away from the Electoral College would be immense.

When it comes to other structural issues with the Electoral College, we find majorities are concerned that less populated states have too much power (53 percent to 38 percent) and that candidates focus too much on swing states (54 percent to 38 percent) because of the Electoral College. These concerns exist because of the Electoral College process and will continue to be a source of concern as long as it remains.

We find especially strong concerns over highly unlikely scenarios that are owed to the events surrounding the 2020 election and its aftermath. Interestingly, these worries cross party lines with members of both tribes expressing unease that they could happen.

Nearly three-quarters (73 percent) of respondents say they were concerned that a state legislature could overturn their state’s popular vote for president. This translates to 86 percent of Democrats, 72 percent of Independents, and 62 percent of Republicans. Overtures by the Trump campaign were made to state legislators to consider doing this after the November 2020 election.

Seven in 10 respondents stated that they were concerned that Congress could overturn the results of the November election when they meet to count electoral votes on January 6 after the election. This anxiety is undoubtedly triggered by the events of January 6, 2021. A large majority of Democrats (80 percent), Republicans (64 percent), and Independents (69 percent) share a common concern over such an unlikely event occurring. In an attempt to prevent another January 6, Congress passed the Electoral Count Reform Act of 2022 to make it harder to challenge electoral votes and have them discounted during the joint session of Congress.

Lastly, 62 percent of respondents are worried about the potential for so-called faithless electors who do not vote for the candidates to which they are pledged. In 2016, a record number of faithless votes were cast. In 2020, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments as to whether states could prohibit faithless electors and ultimately, they decided that they can. As a result, many states have passed laws prohibiting faithless votes, making their appearance less likely.

While most arguments over the Electoral College focus on whether or not we should select our presidents by a national vote, it appears that most citizens are concerned with various manipulations of the Electoral College process under certain conditions. The stress tests we have seen in recent presidential elections have made these concerns much more salient and the potential for several of them—such as another misfire election—will persist under the status quo.

Robert Alexander is a professor of political science at Bowling Green State University. He is the author of Representation and the Electoral College, published by Oxford University Press.

Anna Dawley is a prelaw student at Bowling Green State University with majors in political science and English along with a minor in Spanish.

The views expressed in this article are the writers’ own.