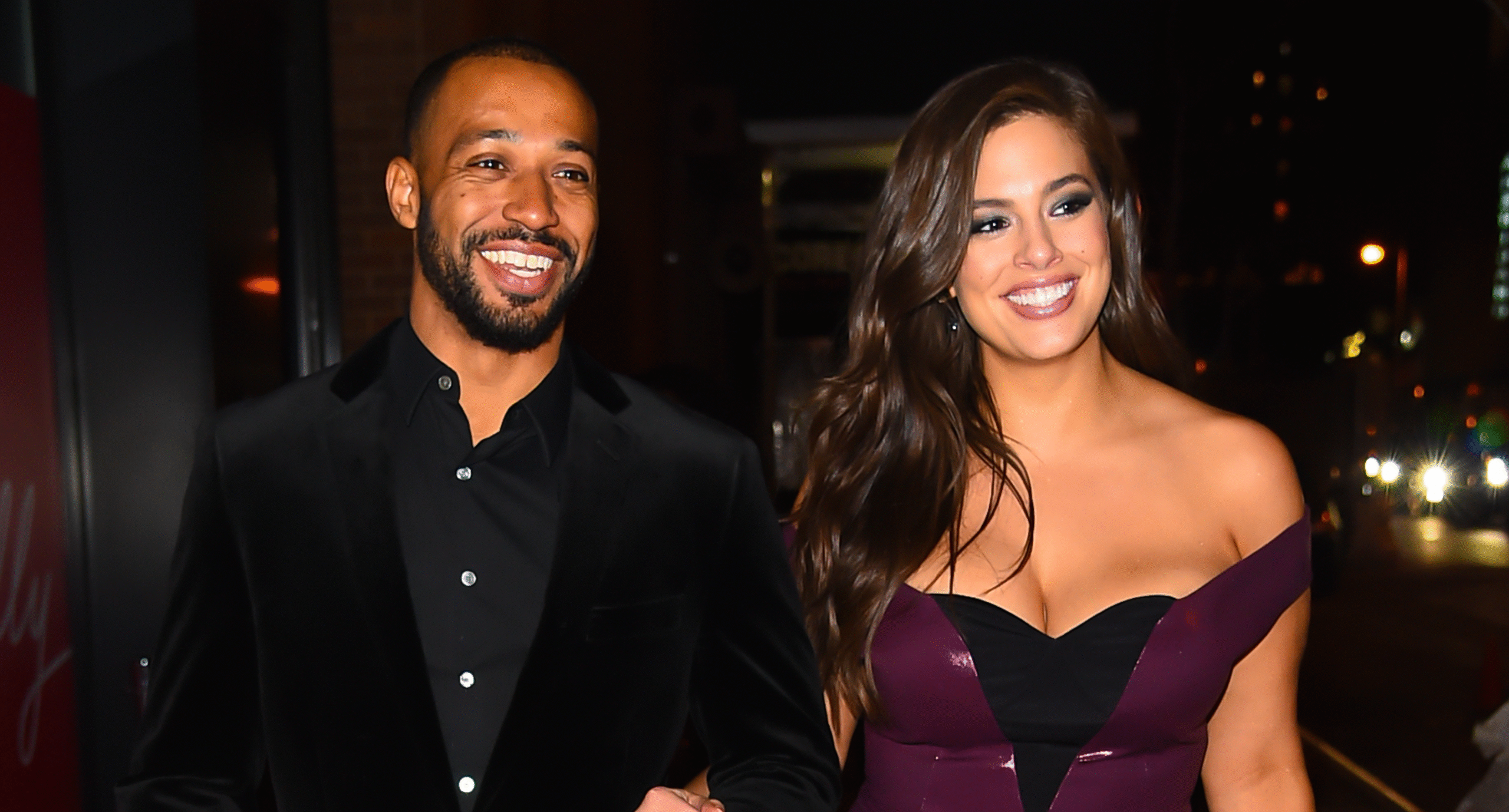

Model, actress and entrepreneur Ashley Graham revealed last week that she and her husband, Justin Ervin, have deliberately chosen not to tell their 3-year-old twin sons, Malachi and Roman, who arrived first.

During an interview with Dr. Aliza Pressman, the author of “Raising Good Humans”, Graham explained that by withholding this detail, they hope to avoid fostering an “I’m older than you” mindset, even though, for context, Malachi was born before Roman.

“They won’t know until they read an article where I shared who did come out first,” Graham told Dr. Pressman.

Getty Images

“Even without knowing, they still all act according to their birth order, which is hilarious,” she continued. “But we treat them the same when it comes to camaraderie and playing together. We make sure they know, ‘That’s your brother. This is your family—support each other, help each other out.'”

Dr. Katie Barge, chartered psychologist, told Newsweek that children often internalize labels such as “the older one” or “the younger one,” which can shape how they see themselves, like taking on responsibility earlier, or being seen as the “baby” of the family.

She pointed to research from 2020 that showed adults’ responses to labels shape roles; when ‘older’ is always seen as more capable, it can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy like the ‘Pygmalion effect,’ where expectations influence opportunities and feedback.

“If parents withhold [which child] is older it can reduce the pressure of these roles and give children more freedom to develop their identity based on temperament rather than expectation,” Dr. Barge said.

On the flip side, this could also be seen as an advantage for children by helping them to avoid fixed roles like ‘leader’ or ‘follower’, promoting equality, cooperation and respect.

“However, the drawback is that children are very perceptive,” Dr. Barge said. “If they sense information is being withheld, it could cause frustration, lack of trust or curiosity. Ultimately, the family’s openness and attitude matter more than the fact of who was born first.”

Both observations highlighted that it’s not simply about what’s known but what expectations are created—or avoided.

For years, people have believed that firstborns are naturally more responsible, while younger siblings are more carefree or rebellious.

But modern research suggests that birth order doesn’t strongly shape personality in the way many assume.

One of the largest studies to date, which analyzed data from over 20,000 individuals across the U.S., UK and Germany, found little consistent evidence that being first, middle or last born affects traits like confidence, agreeableness or ambition.

When it comes to twins, being born first can sometimes matter in the delivery room—for example, the firstborn twin may have slightly better health scores at birth.

But as they grow up, differences in personality are usually shaped more by temperament, parenting and family dynamics than by who arrived first.

In other words, siblings (and twins in particular) often develop their own roles naturally, but these roles come from who they are and how they interact—not just from birth order.

Even without explicit labels, kids find their place. “One may take on a caregiving stance, another may push boundaries,” Dr. Barge said. “This reflects both their innate temperament and the ‘system’ of family dynamics, for survival and attention.”

She explained that parents can support healthy sibling relationships by:

- Avoiding comparisons (“she’s the responsible one, he’s the funny one”)

- Encouraging flexibility (all siblings get chances to lead and follow)

- Valuing individuality over role (“I love how you approach this”).

Steven Buchwald, a psychologist at Manhattan Mental Health Counseling, called Graham’s choice “unconventional yet thoughtful.”

He told Newsweek that by removing the layer of hierarchy, Graham and her husband are choosing to give their twins the space to grow into their own identities without the pressure of a birth-order narrative.

“This decision may help reduce unnecessary competition and foster a sense of equality between the children,” Buchwald said. “However, it’s also important to remember that siblings naturally seek differences to define themselves, so parents should still remain attentive to ensuring both children feel equally valued and heard.”

To ensure parents enable their children to be equally valued and heard, Buchwald advised:

- Celebrating each child’s strengths—rather than comparing them to one another.

- Offering equal opportunities and praise—to foster mutual respect and diminish rivalry.

- Normalizing differences—help children understand that being different isn’t inappropriate; it’s healthy.

- Staying flexible and intentional—parenting requires adaptation; what matters is the consistency of care and support.

Buchwald argued that Graham’s parenting shows parents can challenge norms to benefit their children’s emotional growth.

“What matters most is not whether children know ‘who came first,’ but whether they feel equally loved, supported and encouraged to develop their own unique strengths,” he said.