The share of Americans aged 65 and older who remain in the workforce has reached historic highs, with recent data mapping significant state-by-state differences.

A recent analysis by Assisted Living Magazine (Assists) found that more than one in five older Americans choose to work past the traditional retirement age, with Northeast states seeing the largest proportions of seniors forgoing retirement. These trends have sparked new debates over financial security and the structure of the United States’ retirement system.

Why It Matters

The increasing number of seniors choosing—or needing—to work past their mid-60s underscores deep challenges in retirement planning and the evolving economic realities facing older Americans. With the nation’s population aging rapidly, these trends impact not only the personal finances and well-being of millions but also workforce dynamics, employer strategies, and public policy.

The rising cost of living, prolonged life expectancy, and shifts away from guaranteed pension plans toward 401(k) retirement savings have created new pressures and reshaped what it means to retire in the U.S.

What To Know

Federal data showed a dramatic surge in the number of employed Americans aged 65 and older over the past decade. Between 2015 and 2024, workforce participation among seniors increased by more than 33 percent, compared to a growth rate of less than 9 percent in the overall workforce, according to a February report by CNBC.

By 2024, seniors accounted for 7 percent of all workers nationwide. Economic necessity, longer life spans, and changes to Social Security policies were among several factors leading Americans to work longer than previous generations.

A report from Assisted Living Magazine found that a record 11.2 million Americans aged 65 and older are currently in the workforce, and this number is projected to rise to 14.8 million by 2033.

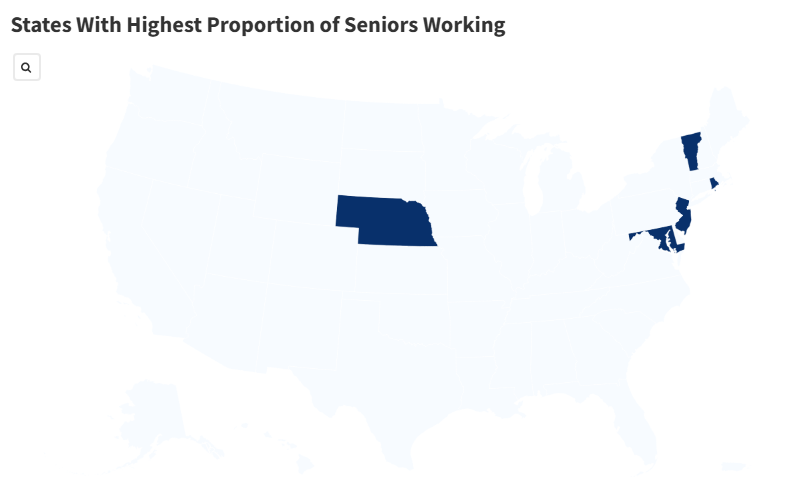

The states with the highest proportion of seniors in the workforce include Vermont, Nebraska, Maryland, New Jersey and Rhode Island.

Vermont topped the list, with 25.8 percent of its seniors still working, while Nebraska saw 23.9 percent of its seniors continuing to take on jobs past retirement age.

The cost of living and the types of industries that are popular within a state can impact whether seniors stay in the workforce. As Nebraska’s farming communities often require seniors to continue working if they are able, there will be a higher percentage.

Northeast states generally saw higher numbers of seniors in the workforce, with New Jersey and Maryland at 23.8 percent and 23.7 percent, respectively.

In states with a high cost of living, retirees may choose to continue working to earn extra income, allowing them to maintain their standard of living. White-collar jobs, which comprise many of the roles in these states, also offer added flexibility that can enable seniors to work for longer.

Rhode Island had a senior labor force participation rate of 23.7 percent, whereas states like West Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Arizona had the lowest senior workforce rates, ranging from roughly 13 to 15 percent.

Many older workers reported working to cover living expenses as inflation strains fixed incomes and as fewer Americans are able to rely on traditional pension plans. Social Security benefit changes—raising the full retirement age to 67 for those born in 1960 or later—also create incentives for delaying retirement.

“While Social Security and Medicare certainly help seniors in their later years, the reality is costs for some exceed those benefits and staying in the workplace may be more of a requirement than an option,” Alex Beene, a financial literacy instructor for the University of Tennessee at Martin, told Newsweek.

Potential Benefits of Seniors Working Longer

An August 2024 University of Michigan poll of U.S. adults aged 50-94 found that 71 percent of workers over 65 believed their jobs had a positive impact on their mental health, while 67 percent cited physical health benefits, according to U.S. News & World Report.

Nearly a third reported struggles due to disability or health problems, but the majority described working as beneficial.

What People Are Saying

Jeremy Clerc, the CEO of Assists, told Newsweek: “We’ve seen firsthand that more seniors are working longer, but what did catch our attention were the regional disparities. States like Iowa and Nebraska having workforce participation above 23 percent for seniors, signals something deeper than just financial need. It reflects things such as strong local economies, better access to part-time or flexible work, and in some cases, cultural expectations to stay active.”

Alex Beene, a financial literacy instructor at the University of Tennessee at Martin, told Newsweek: “The common theme of the states that have a lower participation rate of seniors in the workforce is a lower cost of living. States like West Virginia and Mississippi benefit from less expensive costs on everything from food to housing. Other states, particularly in the Northeastern United States, are seeing an influx in workers over the age of 65 due to rising costs.”

Michael Ryan, a finance expert and the founder of MichaelRyanMoney.com, told Newsweek: “This is a sign of the times. In many states nearly a third of retirement aged are still working, and it’s rising fast. The old idea of a gold-watch retirement is fading, replaced by a new reality where work is both a necessity for some, and a source of purpose for others.”

What Happens Next

With record numbers of Americans turning 65 in the coming years, the trend of seniors staying in the workforce is projected to continue.

Policymakers, employers, and advocacy groups are expected to focus on supporting older workers, addressing ageism, and adapting retirement planning to the new demographic and economic realities mapped out across the U.S.

“We need to build more inclusive economies for aging Americans. That includes age-friendly workplaces, accessible public transportation, and retirement models that allow for phased transitions instead of a hard stop at 65,” Clerc said. “Seniors are telling us they’re not done yet—the systems around them need to catch up.”