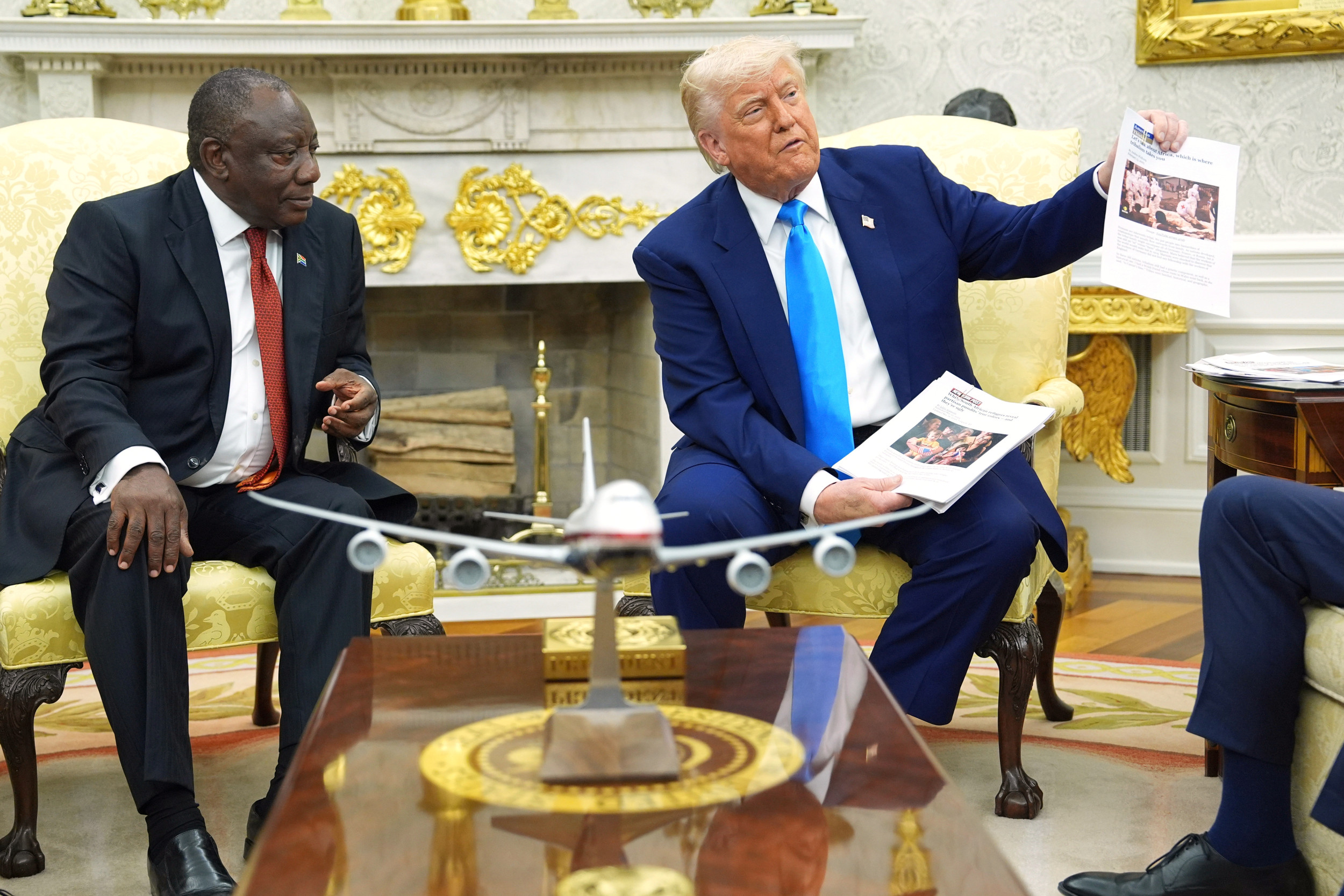

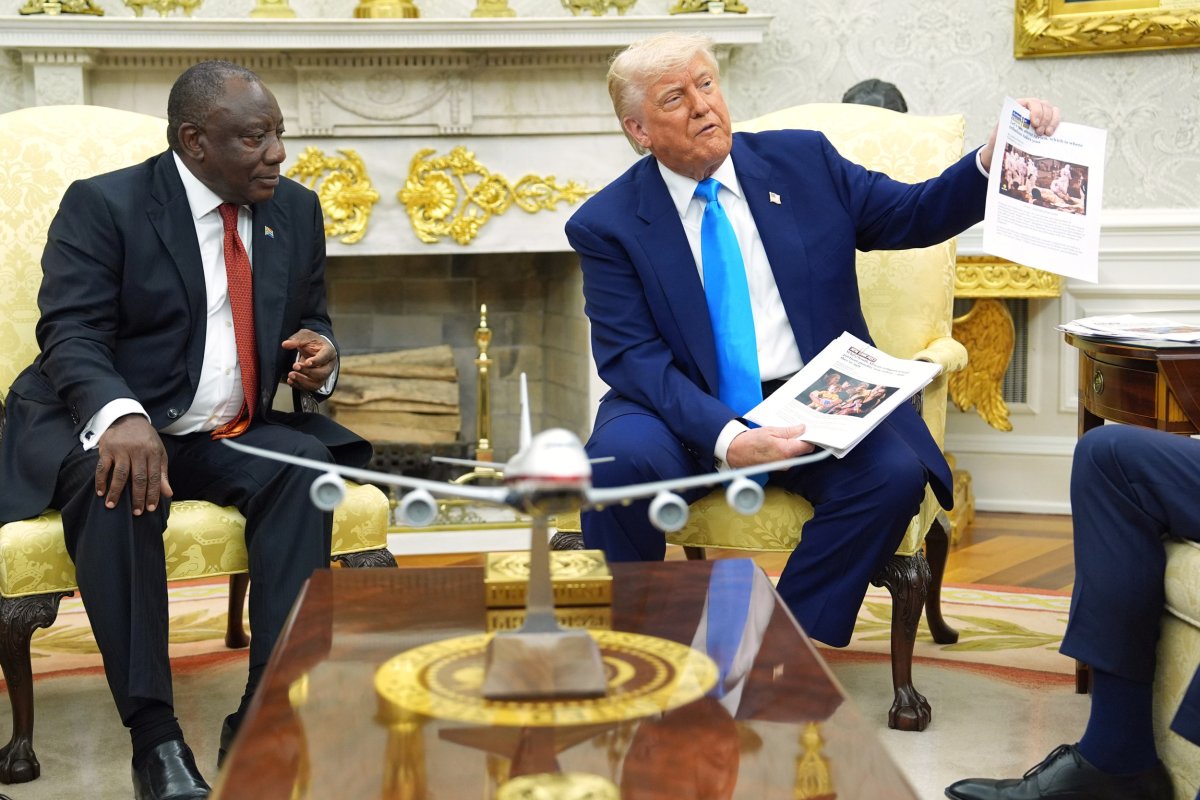

In a tense White House meeting with South African leader Cyril Ramaphosa, President Donald Trump showed footage of two South African politicians chanting “kill the boer, the farmer.”

The chant is a legacy of the struggle against white majority apartheid rule, and Trump asked president Ramaphosa why they had not been arrested.

The Context

Ramaphosa met with Trump in the Oval Office on Wednesday, amid high tensions between the two countries, namely over America’s classification of Afrikaans farmers as victims of a “white genocide” and “refugees.”

When the pair got to this topic, Trump paused the meeting to play a video that alleged “white genocide.”

The four-minute clip featured a series of snippets of Jacob Zuma, the head of uMkhonto weSizwe (once the fighting wing of the African National Congress), and Julius Malema, the head of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), chanting “kill the boer, the farmer” and talking about land expropriation—an issue that has plagued South African politics since the end of apartheid just 31 years ago.

Ramaphosa responded, saying that the speeches by the growing opposition party leaders shown in the video were “not government policy,” adding: “Our government policy was completely against what he (Malema) was saying.”

“They are a small minority party,” Ramaphosa added, before attributing the killing of white farmers to “criminality in our country.”

South Africa’s Minister of Agriculture John Henry Steenhuisen also responded, saying: “We have a real safety problem in South Africa. I don’t think anyone wants to candy-coat that.”

He later added: “The two individuals that are in that video that you’ve seen are both leaders of opposition minority parties in South Africa uMkhonto weSizwe under Mr. Zuma and the Economic Freedom Fighters under Mr. Malema.”

“Now the reason that my party the Democratic Alliance (DA), which has been an opposition party for over 30 years, chose to join hands with Mr. Ramaphosa’s party was precisely to keep those people out of power.”

When a member of the American press asked Ramaphosa if he denounces the language used in the video, he answered: “Oh yes, we’ve always done so … we are completely opposed to that.”

Trump then interjected with the question: “But why won’t you arrest that man?”

South Africa’s courts have been grappling with this question for more than two decades—here is everything you need to know about it.

AP

History of ‘Kill The Boer’

The phrase originated from an anti-apartheid isiXhosa protest chant— “Dubul’ Ibhunu,” which translates directly as “kill the boer.”

It was chanted in protest against white minority rule, which enforced segregation and denied South Africans of color basic political rights, freedom of movement, access to quality education, health care and land

It was widely sung throughout the 1980s and 1990s, during the peak of the anti-apartheid struggle.

Malema started singing the song again in 2010, when he was the head of the ANC’s Youth League, according to South African outlet the Daily Maverick.

In response, the Afrikaans civil rights group AfriForum took Malema and the ANC to court which was the start of a long-standing legal battle about the chant that was ruled on by the Supreme Court on March 27 this year.

What South African Courts Say About ‘Kill The Boer’

Although the South African Supreme Court ruled on this case just a few weeks ago, issuing a final refusal of leave to appeal, the crux of the case was decided in 2022, when the Equality Court of South Africa ruled that the chant does not constitute hate speech.

Malema argued that the chant was not literal, rather that it was “directed at the system of oppression.”

As an example of this, he told how, “when Black police drove into the Black townships with police vans, they used to run and say there comes the ‘Boers’ even when there were no white people in the vans,” Judge Edwin Molahlehi summarized in his judgment.

Malema “testified that he understood (the chant) to be referring to farmers who represent the face of land dispossession.”

Malema “also accepted that the chant was intended to agitate and mobilize the youth to be interested in the struggle for economic freedom,” Molahlehi wrote.

Meanwhile, Afriforum argued that the chant is “sung in a climate or environment where farmers are frequently tortured, and murdered and thus that is good reason to believe that the words chanted by Mr. Malema and EFF call on people to kill farmers and amounts to the promotion of hatred on the grounds of race and ethnicity and constitutes incitement to harm.”

While Molahlehi found that the chant “may well be found to be offensive and undermining of the political establishment,” he ruled that Afriforum could not “show that the lyrics in the songs could reasonably be construed to demonstrate a clear intention to harm or incite to harm and propagate hatred.”

The decision has not quelled the controversy around the chant, with the DA, South Africa’s long-standing official opposition party, saying in a statement earlier this year that it has “no place in our society, regardless of any legal ruling on its constitutionality.”

“This type of divisive language is not just damaging on a local level, it has international repercussions as well,” the party said. “South Africa’s reputation on the global stage is at risk when such hatred is openly condoned, making our country more vulnerable to external scrutiny.”

“We cannot afford to further polarize our society or undermine the international standing we’ve fought so hard to build,” it added.

Newsweek has contacted Ramaphosa’s spokesperson, via email, for comment.